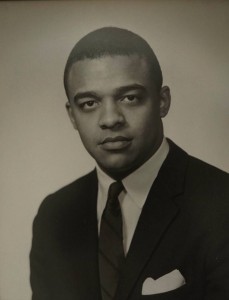

Everett N. Kelsey, Sr.

FAST-MOVING BANKER ABROAD

Source: EBONY Magazine. Dec. 1967, Vol. 23 Issue 2, p41-46. 4p.

IT HAS never been Everett Newton Kelsey’s habit to wait a long time before getting things done. At 16 he was out of high school. At 19 he graduated from Hamilton College. At 20 he was an officer—an ensign—in the Navy. At 24 he had a Columbia University master’s degree in International Affairs. At 25 he was off in Africa, a Ford Foundation Fellow helping Tanzania through its first years of independence. At 26 he’d been hired for management training by New York’s Chase Manhattan Bank—which, with $17 billion in assets, crowds Bank of America’s position as the biggest in the world. At 28 he had been sent overseas by Chase as assistant manager of its Paris branch.

Now, at 30, Kelsey sits in a Rue Cambon office overlooking Ernest Hemingway’s favored Ritz Hotel Bar and handles major aspects of the branch’s business with such industry giants as Ralston-Purina, Caterpillar, Shell-British Petroleum, Mobil Oil, ITT and the French-American electronics manufacturer, Bull-GE. These corporate clients and about 45 others in his portfolio can call on Kelsey for every banking service—from setting-up new accounts to providing information about, say, Common Market trends and the policies of the German Bundes Bank; from giving advice on investments and markets to approving lines-of-eredit for another year. Kelsey is expert in each such area, but his specialty is commercial loans. This year his approvals resulted in more than $30 million of Chase money being made available to businesses in England, France, Belgium and other countries of Europe. In just two years there, he has become the leading loaning officer at the Paris branch.

Kelsey-who was born in Atlanta but grew up in Madison. N. J., where his father, the theologian Dr. George D. Kelsey, has the Christian Ethics chair at Drew University-got into international banking in a roundabout way. It was the political side of international affairs-especially the politics of emerging Africa-which interested him back in 1957 when he was graduated from Naval Officers Candidate School at Newport, R. I., and went aboard the U.S.S. Cassin Young, the 2.100-ton destroyer on which he served for two years. The African freedom movement had begun; independence talk was in the air. At sea, Kelsey read everything he could find on Africa and the politics that was wresting it from colonial rule. But then, out of the Navy and at Columbia Graduate School (where he headed his class and was editor of the university’s Journal of International Affairs), pulled back a little from political Africa and centered his interest on the fundamental economic problems that the continent faced in a highly competitive world. “I saw the absence of whole industrial sectors in those economies,” he recalls, “and saw opportunities for development that would enormously benefit the people down there. I could see that, despite all the concern with politics, the key to a better life for the people lay in the economic sector. Perhaps banking and finance and the utilization of capital were at the back of my mind even then.”

After graduate school, Kelsey worked for a while as a research associate for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and wrote Africa-oriented articles for International Conciliation. Then he became the first African-American ever selected as a Fellow of the Africa-Asia Program, the Ford Foundation-sponsored program which is administered by the Maxwell School of Public Affairs at Syracuse University, and which each year selects 10 or 12 of the top men from the best graduate schools and prepares them for service to governments in developing countries. The government of Tanzania picked Kelsey to work as a civil servant in its Ministry of Community and Cooperative Development, and off went he and his wife. Olive, and their daughter, Holly, to live in Africa for a year and a half. Kelsey was district cooperative officer in the Mwanza District of northern Tanzania. He dealt with farmers and their agricultural marketing co-ops, took charge of five inspectors, approved budgets, hired staff and supervised distribution of profits of the co-op scheme. At 24, he was, to Africans, still “a small boy.” But by dealing squarely with the farmers, he won the respect of the nearly 300,000 people with whom he was involved.

Kelsey remembers: “I’d put on short khaki pants and get around over some pretty rough roads to talk to about 100 farmers meetings a year. You know what we’d do? We’d find ourselves a big mango tree and everybody would sit down on the ground while I stood at a blackboard and talked about such things as profits and investments and why cotton prices were so low on the world market. The people were largely illiterate, but they were the savviest people I’d ever known. They’d fire all kinds of really tricky questions at me, and I had to give them the right answers if i wanted to keep them believing in what I was trying to do.”

Not only the Africans believed in Kelsey. One day while he was out in the bush with his farmers, a message came from Adlai Stevenson back in New York at the U.N. Stevenson wanted Kelsey there as a political officer. “It wasn’t a bad offer,’ says Kelsey, but turned it down. I’d been in Africa long enough to see how interested the people were in helping themselves, how much they needed, and what could be accomplished if their resources and capital were handled right. And “handled right’ follows, you know, whether we’re talking about poor people’s resources and capital in Africa or Latin America or in Harlem, U.S.A. So I turned down the U.N. offer because I wanted to look around for an area in which I might someday influence the availability of private capital to individuals and business groups that want to work outside of government-controlled development plans.”

When his Africa work was finished, Kelsey came back to New York and was snapped up by Chase Manhattan for his rigorous Special Management Program. He was, finally, in the area that by now seemed most important to him: banking and finance. He joined Chase in October. 1963, and it was another “first” for him: the first African-American ever hired for what is supposedly the “best bank officers training program in the world.” For six months he went from one Chase department to another, familiarizing himself with the huge bank’s organization and with such things as accounting and finance analysis. Then he moved into the credit department as a credit analyst. For 18 months he worked alongside experienced bank officers in analyzing corporate loans and in learning all aspects of Chase’s worldwide corporate lending activity.

Even before his training was completed, Kelsey got a chance to prove what he’d be able to do. Two big companies had drawn up a complex arrangement by which they could force each other to either sell all shares or buy up all shares in a milk company in which they had invested. Millions of dollars were involved, and the outcome depended on which company was shrewdest in evaluating the milk company’s worth. One company was a Chase client. It turned to the bank for advice. The Chase vice president in charge of the account called in Kelsey. “It’s your baby,” he said, “so get moving on it.” Kelsey had just 18 days to develop a philosophy of the analysis, to decide the best way to approach it, to call in information from Chase’s formidable research staff, then digest everything into a short, readable report. He remembers the day that he and the Chase vice president (who trusted him enough to never ask to check the report) were summoned to the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel: “The client’s top officers were enroute to a board meeting in the Caribbean, and they wanted that report without any excuses. We got to know one another over about six martinis, then I got up and gave my little speech.” What Kelsey had come up with was a report that was less then one typewritten page. But it was backed up with all the statistics, tables, research, information etc. that the client’s own analysts would demand. After several months of suspense, Kelsey learned that a deal had been made with only a $2.00 difference in the share value he had recommended. “It’s not bragging to say that it was an incredible result,” he says. “That was only a 2% variance in a deal where even as much as 15% wouldn’t have made me look bad.”

Not long alter that problem-solving coup Kelsey was moved up to his Assistant Manager post and sent to Chase’s $220 million Paris branch. There, he is—as are few African-Americans—one of the new breed of young, successful American men who are making important decisions in international corporate affairs. The betting is that he will be a Chase Manhattan vice president before too long.